When Consensus Strategies’ SVP Owen Eagan isn’t managing your projects, he is an Executive-in-Residence at Emerson College, the nation’s only four-year institution dedicated exclusively to the study of communication and the performing arts. Recently his latest book, Oscar Buzz and the Influence of Word of Mouth on Movie Success, was released. Below, we are proud to give you a preview. – Pat Fox

What best determines a movie’s success?

The title of this article refers to a question that I typically pose to my students. Specifically, I ask them, “What best determines a movie’s success? Is it the genre, director, producer, cast, budget or something else?”

Their responses are intelligent and well-articulated, especially since each of these factors has a significant influence. However, they rarely get the right answer. In fairness, they’re not really expected to know, especially since many movie industry professionals don’t know either.

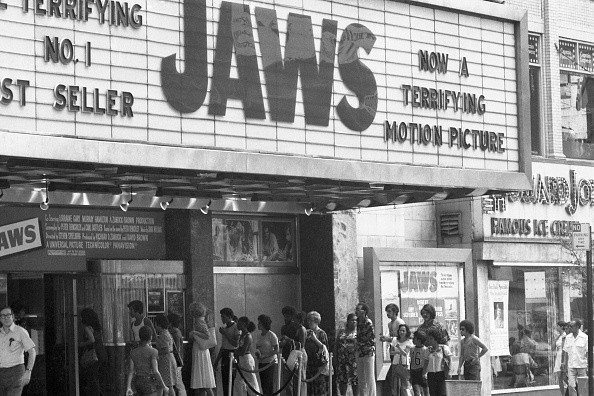

The answer is word of mouth, which has been well documented by academic studies and industry experts alike. Let’s compare and contrast two movies as an example.

The first movie is John Carter, a science fiction movie produced by Walt Disney Studios in 2012, which was a box office disaster. It was reported that the company lost $200 million on the film. The other movie is Paranormal Activity from 2009, which was produced for $15,000 and earned $194 million at the box office. As a result, it became the most profitable movie ever made.

John Carter had all of the ingredients for a box office success. It was based on a popular book by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the renowned author of the Tarzanseries, called A Princess of Mars. It had an Academy-award winning director in Andrew Stanton who directed Wall-E and Finding Nemo. It featured major stars including Taylor Kitsch and Willem Dafoe. And it was financed by Walt Disney Studios.

Conversely, Paranormal Activity had none of those ingredients.It was entirely written and produced by Oren Peli, a former software designer, and was filmed over seven days and nights at his house in San Diego. Its stars were newcomers Katie Featherson, who worked as waitress at Buca di Beppo at Universal CityWalk, and Micah Sloat, who was a computer programmer.

While these movies represent the extremes, there are numerous other blockbusters and bombs that have followed similar patterns. This is due to the unpredictable nature of movies. In fact, it has been estimated that six or seven out of ten movies are unprofitable and one might break even.

This volatility in the movie industry was best captured by Academy-award winning screenwriter William Goldman in his 1989 book Adventures in the Screen Trade. Speaking of the film industry, Goldman famously stated, “Nobody knows anything.”

Other leading experts in Hollywood acknowledge the unpredictability of movies. On this subject, Tim Gray, the Awards Editor and Senior Vice President at Variety, likes to quote Sydney Pollack, the award-winning producer, director and actor. Said Pollack, “I’ve made big hits and I’ve made terrible flops. And I don’t know the difference.”

In a landmark study published in 1996, Arthur De Vany of the University of California at Irvine and David Walls on the University of Hong Kong analyzed movies from May 1985 to January 1986 and discovered that 80 percent of the revenue was generated by 20 percent of the films. However, they were unable to determine why audiences were attracted to some films and not others. They found that because people won’t know if they like a movie until they’ve seen it, word of mouth had a significant influence on a movie’s success.

In light of that research, my students and I conducted a number of studies at Emerson College to find further evidence of this phenomenon. One of our studies analyzed the extent to which highly anticipated movies lived up to their hype.

Specifically, we found that movies with the biggest opening weekends lost more revenue in subsequent weeks than those movies with the biggest second, third and fourth weekends on average. However, the average Rotten Tomatoes scores of both critics and audiences inversely increased for these movies.

So, as revenue inversely went down, reviews inversely went up. This suggests what is technically called an information cascade which can be easily broken when people’s experiences don’t meet their expectations.

Next, we wanted to know if there was any evidence of word of mouth that could be found among high-performing movies and low-performing movies. Because movies are so subjective, defining these categories was our biggest challenge.

We decided to use films nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, known as an Oscar, and those nominated for a Golden Raspberry Award, known as a Razzie, which recognize the worst movies of the year. Over a 20-year period, we found that Razzie nominees lost an average of 30 percent more over the first four weekends compared to Oscar nominees.

The revenue changes of these movies were very consistent week-to-week which suggests that whether moviegoers recommended or didn’t recommend them had a significant effect.

As another means of testing this hypothesis, we analyzed the tweet sentiment and the tweet rate of movies to see if there was a correlation with box office revenue. Our research revealed that there was a strong relationship among both. This is not surprising as Twitter has been used successfully as a predictive model for other purposes such as predicting changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

We also explored other variables including the influence of film critics. Using Rotten Tomatoes scores, we found that film critics had a moderate influence on wide releases and a slight influence on limited releases. This was true for both opening weekend and total revenue.

However, we found that in both instances negative reviews had more of an influence than positive reviews. This is due to a negativity bias which stems from the concept of loss aversion. This concept states that people have a greater aversion to losses than they have an affinity for gains.

It was discovered as part of prospect theory by the Nobel Prize-winning economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. This is why people typically hold on to depreciating stocks longer than appreciating stocks.

Nevertheless, despite the limited influence of film critics, we wanted to know what this meant in terms of revenue. As a result, we conducted a test to determine the difference in revenue between the movies with positive and negative reviews.

Only the wide releases had a statistically significant difference. The difference was $23 million for opening weekend and $83 million for total revenue, which meant that film critics’ moderate influence could have a significant revenue impact on movies.

Although, as vital as film critics are, their impact is still not as significant as the influence of word of mouth. At least when it comes to movies, everyone’s opinion matters.

You can learn more about this subject as well as how to reduce risks and other variables in my new book by Palgrave Macmillan entitled Oscar Buzz and the Influence of Word of Mouth on Movie Success.